It is very interesting to analyze thoughout all of two videos. By both we can understand what we are expecting about the city planning (metàpoli?) almost respect and willingness towards their inhabitants. The despotic enlightenment is killing Democracy. Willpower, needs, participation, sharing or annoucements of inhabitants-users are not rather important onto star-hypotheses. The least for social conditions. I have even remembered the Bohigas’ speech who said there far “qui hi sofreix la degradació urbana n’ha de rebre-hi les plusvàlues generades”.

La reconstrucció de Barcelona. Edicions 62. 1980. These deep throughts were a wholly declaration of war against Barcelona’s speculators. There is also unaware items about that issues at this snobbish vultures. See you second video when he had been telling about Sociópolis on the equalitaty sharing of benefits to build. This is the newer boss in planning Barcelona. We will be aware toward lacks owing to disappointment with another old leaders like Bohigas, Borja, etc. and current thinckers.

Our urban planning, like someone, must be another ways.

From the indignant inhabitants rising up. Sharing and consultant from citizens-users. I will want paying attention. Sociopolis was shown first few years before to Pobla de Vallbona’s Council, but it was rejected. Afterward was presented at Generalitat for staying on a suburban zone named La Torre, small village next to València City. Valencian Generalitat needs at that moment cleans up its folcklorical image. Valencian Generalitat thought over the project themself. Always both friendships get on with when they put on contrysides good at agriculture production. Never when there are problems. At the beginning,at first they have created the abstract solution, later they come back to look at about few places for implementing their shady thoughts. A lot of their ideas were alredy in Russian Constructivists early of twentieth century or Le Corbusier’s, or rather in movement of Bauhaus’ artists amongs everyone. There’s nothing never under sun. You don’t see them in any conflict that people suffers attacks from the powerful Hand. Forever together within It.

The

speed on urbanism works against willpower of people, in fact, against Democracy. They hardly allude in concrect for human beings, but if would be able, that was only like the alibi of guilty.

What the pity Barcelona….and poor València !

When I was a student named them, the mixed group, more or less,

as

The reactionary avantgarde.

http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=ca&sl=es&tl=ca&u=http%3A%2F%2Fblog.bellostes.com%2F%3Fcat%3D52&anno=2

I am not alone..there are a lot of European architects that are getting hate at this fals state of aims. TRUE INNOVATION needs to project on matter more human collective and single than a reason oneself. For me, the raw material in architecture is human being inside the whole world. Arts needs social pleasure, the opposite is only a holding of games to masturbate. Keep on to read more..in ” Vull llegir més..:”

GeoLogics:Geografía-Información-Arquitectura de Vicente Guallart from WebMaster on Vimeo.

From Political Games to Absolute Architecture … and Back – The Architectural Avant-Garde Today

by BAVO

Nothing. It was not my aim that he feels anything. I had only the aim to impose the grandeur of the building upon the people who are in it. If people who may have different minds are pressed together in such surroundings, they all get unified to one mind. That is really all.

Albert Speer when asked for the effect of architecture on the user. [1]

1. I will not apologize for what I am! Respect the cock!

In the last decade, a real exodus has taken place among the architectural avant-garde, not only to ‘allied’ disciplines such as design or urbanism, but also to geography, philosophy, art, photography. Avant-garde architects started to occupy themselves with everything except architecture in the strict, traditional sense. In an obscure, self-destructive mood, architects themselves shifted the focus away from their own discipline and turned to what they called ‘architecture without architects’, ‘do-it-yourself architecture’ or even ‘architecture against architecture’ [2]. Whether it concerned the endless megalopolises in China, shrinking cities in Eastern-Europe or illegal buildings in post-war Balkan, everywhere architects were eager to map these fascinating processes, to photograph the unplanned urban developments with a wide-angle lens from a helicopter, to simulate the built reality in 3D-models and so on. Based on these registrations thick books were produced that reported from a world where, so they stressed, architecture with a big A played absolutely no role whatsoever, and where the traditional role of the architect is being taken over by a heterogeneous group of engineers, developers, marketers, hobbyists and what not. Every time the discussion focused too much on architecture with a big A, architects hurried to stress that 99,9% of the population is not ‘into that’, that most part of the crust of the earth is covered with what the architectural profession would label as ‘pulp’: suburbs, slums, generic shopping malls and so on. In short, in cutting edge architectural circles it had become the norm to affirm everything whatsoever as architecture except… architecture itself! To summarize my point, we can say that the last ten years the seemingly liberating affirmation that ‘everything is architecture’ was paradoxically accompanied by the constant warning that ‘architecture is not everything’.

Of late there has been a growing resistance against this ‘evacuation of the discipline’. This is already obvious from the fact that after the years of aggression and self-hatred against the Master-Signifier ‘Architecture’, today it has been restored to its former glory. Either it is ‘elevated’ – think, for example, of the recent plea of architecture theoretician, Pier Vittorio Aurelio for an ‘absolute’ or ‘pure’ architecture [3]. Or, it is caught in tautological constructions such as ‘architecture is architecture’, ‘architecture is itself’, ‘architecture should have the guts to be architecture’, etc. [4] In the latter case, the same tactics are used as in the advertising world where one repeats the brand name over and over again in order to win over the consumer through pure repetition. Both reinvestments in architecture with a big A are definitely therapeutic. Tired of the knots in which one had to tie oneself to legitimize the fact that one just wanted to build or found enjoyment in the architectural text, a growing group of architects started to behave like guru, Frank T.J. Mackey (played by Tom Cruise) in the film Magnolia. [5] As a form of therapy for insecure men that have problems in taking up their phallic funtions, the guru organises sessions in which the men chant slogans together like: “I will not apologize for what I am… Respect the cock… and tame the cunt. Tame it!”. A similar acting-out is now at the order of the day in the architectural world. After the seemingly limitless expansion of the profession in the past decade, a re-territorialization is taking place. Now it is said that the architect should no longer lay down his mandate and flee from his responsibilities, but should learn to accept his socio-symbolic role. It is clear that this is a case of identity politics. Against the year-long imperative of interdisciplinarity, the architect is now charged with doing ‘what he has always done’: design and build. This is seen as the only way out of the years of promiscuous cross-breeding, the only way for architecture to regain its agency.

This retro movement seems refreshing especially when seen against the backdrop of the year-long self-bashing among avant-garde architects. In the latter case one could even speak of a ‘suicide of the profession’ since it is assumed that the architect cannot do more than passively gaze on in fascination as spatial processes spontaneously unfold. It is clear that in this case architecture is deprived of its capacity to actively intervene in society, bereft of its political role to contest and change the existing ideological coordinates. The presumed radical nature of the architectural phenomena that are mapped or charted – such as third world metropolises, illegal markets or shrinking cities – function thus as a mere fetish that hides the fact that on a deeper level the architect qua political subject is thought of as impotent. While this renewed interest in pure architecture may be encouraging, we nonetheless wonder whether this new orthodoxy is the only way to give back architecture its socio-political function. As the tautological construction already suggests, there is a danger that this radical re-birthing of architecture, this search for an architecture that is committed to society, will end up in its opposite: the architect seeking its salvation in a retreat behind the safe and well-tried limits of the profession, countering every criticism as a sign of disrespect towards his professional integrity. In short, the burning question is whether the much needed new commitment to architecture necessarily lies in a new conservatism.

2. The new commitment: the architect should do what it has always done

A paradigmatic example of this re-territorialization is the project Fear of the city (2004) conducted within the framework of Group Portraits for Young Architects 2004 by a group of young architects working together under the name Untitled. [6] Group Portraits is a two-yearly Dutch initiative that offers young architects a chance to produce work on hot social issues. This edition’s theme was ‘Fear and space’ and was obviously chosen in response to the growing unrest and polarization in the large cities in the Netherlands. The first thing that is striking about Untitled’s project is the way in which it delimits its position within the current architectural scene. In the publication, they stress the following: “for too long we kept analysing the city by mapping it, looking for subversive structures, characteristic marginal phenomena, just so we could go on believing that there is still a significant public domain behind the scenes. Having desperately tried to rediscover that city, we started having doubts”. [7] Against this, they plead for a re-investment in architecture qua architecture: “Untitled wants to focus again on the ‘profession’. It wants to regain the ability of being critical within its own medium. It practices architecture as a discipline of space…” [8] This other approach was already obvious from the stark contrast with the other contributions to Group Portraits. While the latter included an alternative sociological model and a public performance, Untitled choosed a straight architectural approach: their project consisted of clean and minimalist architectural models and technical drawings suggesting two alternative architectural typologies for high-rise buildings. Already the titles, Two Towers and one Square and One Tower and one Square, communicate the architectural rigidity of the project.

The second thing that was striking about the Untitled -project Fear of the city was its positive attitude towards the existing context: it wanted to “shamelessly embrace Rotterdam’s dream of becoming ‘a city of towers’ and to bend this force and use it to reshape the public space”. [9] Through an analysis of the cityscape of Rotterdam, Untitled claimed to have uncovered the city’s hidden architectural desire but, as project watcher Bert de Muynck stated: “Not as a ludicrously composed mirror image or missed opportunity, but as a joint, as a possibility to start working with that which exists.” [10] Untitled located the unconscious desire of Rotterdam in its phantasmagoric skyline, and its visible ambition to become ‘the Manhattan of the Maas’. And indeed, Rotterdam is renowned for being the one city in the Netherlands that fully embraces high-rise buildings. This not only as part of the official policy, but also as part of the underground culture: there are for instance several specialized websites where ‘high-rise buffs’ exchange the latest data and discuss the most recent additions to Rotterdam’s ‘skyscape’. Although positive about Rotterdam’s towers Untitled was concerned mainly about the desolate spaces at their base, and their erosive effect on the public space. In these negative side effects, Untitled localised the cause for the popular fears associated with high-rise city blocks and claimed to offer a spatial fix.

Symptomatic for this – as De Muynck called it – ‘in situ therapy’ of Rotterdam [11] was a photograph of the secular towers of Italian Medieval cities such as San Gimignano, shown during Untitled’s project presentation. In view of their methodology, the reason behind the choice of this image is obvious. It suggests that just as these towers are the architectural expression of the desire of the Medieval city communities, so too is it the case for Rotterdam’s longing for high-rise buildings. However, the association with this historical precedent brings us directly to the problematic nature of Untitled ‘sproject. In the first place, it is clear that the Italian ‘cities of towers’ are not so much the expression of the unconscious of the community but of a small minority of merchants who use the towers as status symbols or, to use the current idiom, a public relations strategy. On top of that, the ‘condition of possibility’ of these towers has to be situated in the accumulation of wealth in the hands of this same elite at the expense of the city as a whole. In short, are these towers – hailed and praised in tourist brochures – not an early manifestation of corporate architecture? And does the same not apply to Rotterdam, that other ‘city of towers’ for which Untitled holds an impassionate plea? For instance, one merely has to check the logos on the towers to figure out that the same real estate groups and banks that develop the towers – and so realize Rotterdam’s unconscious desire according to Untitled’s interpretation – are the same power conglomerates, which, with their religion of efficiency and outsourcing, keep an industrial city as Rotterdam in a state of permanent socio-economic insecurity. This is what Slovene philosopher, Slavoj Zizek calls ‘self-colonization’: the mechanism through which multinational operating concerns consider and treat their own country as ‘something that has to be exploited’. [12] Is it not a slap in the face of the better part of Rotterdam’s community to affirm precisely the corporate high-rise as its unconscious desire and make of it the key inspiration for an architectural project that is meant to take away all fear?

From contradictions like this, the basic procedure of new conservatives like Untitled becomes apparent. More precisely, that one should threat buildings independently from their political, economic or, in general, non-architectural aspects such as power, prestige, ideology and so on. To put it bluntly, that one has to look at the city’s architecture as a pure architectural gesture, as a professional idiot. With this, Untitled follows in the footsteps of Rem Koolhaas and his psychoanalysis of Manhattan’s skyscrapers in Delirious New York. [13] Here too we encounter a pure architectural genealogy that lacks any serious consideration of socio-economic or political aspects of the built reality. In both cases the underlying assumption is that something exists like an architectural desire uncontaminated by political or economic motivations. This is clearly a massive reduction of the built reality: it subtracts the most crucial dimension from the city’s unconscious, namely the imprints of socio-economic struggle on its architecture. By focusing on its skyline the unconscious desire of Rotterdam is reduced to the architectural ‘wet dream’ of a small minority of its inhabitants and reinforces an urban history of the ruling upper-class.

It is at this point that the doubt expressed earlier by Untitled about the existence of subversive structures, marginal phenomena or a public space in Rotterdam, backfires on them. They fail to realize that this is the inverted, ‘negative’ manifestation of the same ‘city of towers’ they endorse in their project. To be more precise, the disappearance of public space in Western-European cities is the result of the tendency of the global players behind the city’s development to repress everything that threatens their hegemony outside the borders of ‘Fortress Europe’. It is clear that a substantial public space forms such a threat to the peaceful existence of today’s consumer city. In this sense, it is quite cynical of Untitled to believe that it needs the high-rise ideology to accomplish its own political ambition: the therapeutic cure of the city as a public space. Does it not herewith enter a pact with the devil, if one takes into account that for years now the players behind this ideology have been outsourcing every real public space to other parts of the world? And, should the political role of the architect then consist of providing this ideology with a human and architecturally correct face? To these new conservatives we have one thing to say: know your enemy! Know yourself!

During Untitled’s project presentation one of the commentators – political philosopher, Dieter Lesage – pointed towards the socio-economic processes behind high-rise architecture. [14] For instance, he mentioned the fact that it causes land and property value as well as rent to increase exponentially, which furthers the gap between rich and poor. Indeed, all attempts to domesticate or humanize high-rise architecture by embracing it, seem inevitably to lead to an increase in speculation practices. And thus to the acceleration of the destruction cycle of the building stock, to the erosion of the public space and so on. In this sense, it is not at all clear in what way high-rise architecture would counter the city’s fear as Untitled believes. On the contrary, while it might be liberating for architects to endorse the modernist image of a city of towers, the majority of city dwellers see in it a symbol of global outsourcing, the revision of companies, financial insecurity, job cuts, etc. In this light, Lesage suggested to opt for an alternative urban policy for Rotterdam. Building further on its working class character he proposed to make of Rotterdam a ‘city of poverty’ like Marseille successfully does. He considered this strategy to be more realistic for Rotterdam than trying at all costs to keep up the illusion of being a global city by fulfilling its obligatory skyline. Significantly, Untitled replied that architects should steer clear of political matters, that it is not for the architect to determine community policies. Instead, the architect should stick to what s/he does best: design high-quality, innovative buildings that can be realized within the existing political regime. The bottom-line was that the architect’s involvement in socio-political matters should remain within his/her natural, subservient role.

In this context, one might wonder whether this new conservatism will ever be able to fulfil its ambitions? Did it not desperately want to escape the pitfalls of what they call the mapping approach and to reinvest architecture with the capacity to change and model society through a concrete building project? However, to us it seems that this forced attempt to escape the practice of mapping finally ends up having an equally depoliticizing effect on architecture. To be sure, the year-long scepticism towards architecture with a big A and especially its complicity with the ruling order led to a hysteric and unproductive disengagement from architectural praxis and ultimately to the legitimization of impotence. However, we should not forget that this split discourse certainly had something that is worth fighting for: its heightened awareness of the political function of architecture in the reproduction of the existing power relations. In this sense, we can legitimately ask whether the new conservatives have not thrown out the baby with the bathwater. If so, we should further ask whether this new conservatism in architecture is not in its essence yet another attempt at generating a ‘market difference’ – the attempt of a new generation of architects to create a niche and keep the architectural consumer’s desire alive.

3. Anca Petrescu: spiritual mother of the new commitment in Dutch architecture

In the reasoning of the new conservatives, we encounter the age-old topos of the perverse nature of the architect or more precisely, the phantasm of an ‘other space’. This refers to a political, economic or civil space in which all decisions concerning the organization of society are taken without the architect’s interference. A space, moreover, where the architect qua architect has nothing to say and can only passively look on. According to this phantasmatic scenario, the architect has no choice but to execute the plans of the existing order since he is a mere instrument, a ‘spoke in the wheel’ of society. The only thing that is expected of him is to ensure the architectural surplus-value of the building. This indemnifies the architect against the criticism that, assignment or not, s/he is still responsible for the political or economic implications of her design. For sure, we cannot but admit that the role of jurisdiction and breathing space of the architect today is often very limited. But, is it really true that s/he cannot do anything more than cater to the wishes of the client? He can for instance sabotage the assignment or, in the worse-case scenario, refuse it. However, what the pervert fears more than anything is the loss of enjoyment inherently linked to taking such a firm stance against the employer. Or, in more general terms, what he fears the most is the risk related to acting as a political subject as opposed to a mere instrument of the Other. In short, what is at stake here is the ‘belly of the architect’: performing a radical political act could mean losing the job, being treated as a pariah, getting sanctioned by the board of architects and so on. ‘Self- instrumentalization’ is the only way in which the pervert can solve these risks and secure his enjoyment. However, it is clear that this is a paradoxical enjoyment since it is obtained by voluntarily sacrificing one’s own desire in favour of the desire of the other. This perverse self-reduction can of course be repressed. Think of the typical complaint that architectural practices are mostly the outcome of pre-established demands and expectations with only a minimum of creative input. Still, even if architects generally occupy such a ‘Calimero position’, it still serves as way to legitimize the fact that they actually enjoy an Architecture uncontaminated by political issues as well as an architectural practice that is exempted from having to intervene in the Other Space of society.

By limiting architectural agency in the same, perverse way, the new conservatives join the ranks of architects such as Nazi architect Albert Speer or the Rumanian architect Anca Petrescu. Significantly, the latter recently came to occupy centre stage in Dutch architectural discourse. As is well-known, Petrescu was appointed at a young age by the then-dictator of Rumania, Nicolae Ceausescu to design his so-called House of the People that had to replace the old ‘bourgeois’ centre of the country’s capital, Bucharest. For most, complicity with this project would provide enough reason to whither away in silence afterwards – think of philosopher Martin Heidegger’s retreat after his romance with Nazism in the thirties. Not Petrescu however. After the collapse of the regime, she became the proud defender of the conservation and completion of the building. Up until this day, she still enthusiastically tours the building with interested parties. She is honestly convinced that Ceausescu’s palace is a blessing and a gift to the Rumanian people and the city of Bucharest in particular. Moreover, she is convinced she deserves the gratitude of the Rumanians since they now have a fabulous palace at their disposal thanks to her life-long sacrifice. After all, she managed to keep up with Ceausescu’s whims, to bracket her personal moral principles, and to concentrate on the ‘architectural aspect’ regardless of the rogue character of the regime. And indeed, apart from the parliament the architectural monster now houses one of the biggest conference centres in Eastern Europe as well as a museum for contemporary art. The fact that half of Bucharest had to be demolished first, and that for decades all the country’s resources were sucked into this project, is probably seen by Petrescu as a necessary evil, an inevitable sacrifice for architecture’s sake. In short, Petrescu’s motto seems to be that there is no architectural greatness without bloodshed, no Architecture without dirty hands! [15]

As if this is not bad enough in itself, Petrescu’s legitimization was recently enthusiastically endorsed by Dutch architecture historian, Wouter Vanstiphout. [16] This is all the more surprising since the latter is known in Dutch architectural circles as a progressive force. In 2001, for instance, Vanstiphout was awarded the Rotterdam Maaskant Prize for his engagement in the restructuring of the Rotterdam problem neighbourhood Hoogvliet, amongst other things. This sympathy of liberal-progressivist Dutch architects with their colleagues from the totalitarian tradition is, however, not completely incomprehensible. For years now Dutch architects have warded off every criticism related to the un-kosher character of the employers of their projects or their hidden agendas with the trite retort that architecture is not a profession for beautiful souls or noble principles but comes at a price. In this sense, we can see Vanstiphout’s defence of Petrescu as an ‘answer from the future’. It anticipates the possibility that on a certain day our prosperous liberal-democratic times will be unmasked as a dictatorship of the capitalist market economy. It anticipates moreover the unhappy moment when it will become clear that our Western civilization – including the celebrated Dutch architectural production – is paid for by the ‘blood, sweat and tears’ of the Southern hemisphere’s pauper population. In short, this identification with Petrescu by a prominent Dutch architecture historian, which not only normalizes but ‘hero-izes’ the perverse position of the architect, is meant to neutralize prospective criticisms. It is meant to create a conceptual climate in which it is completely acceptable to turn a blind eye to the prevailing regime’s political or economic corruption while catering to its architectural needs.

Herewith architecture depoliticizes itself even as it presents itself as the only way for architecture to contribute to the ‘good’ of society. The above makes clear that the new wave of commitment ultimately rests on the conservative belief that architecture is unable to really subvert the existing power relations. It has made its peace with the idea that architecture is inextricably bound to the status-quo because the latter determines its content – its programme, function and symbolism. Put bluntly, it argues that if a client asks an architect to build a gambling palace in Las Vegas, the architect can not not build it. He is free to refuse the job of course, but there are hundreds of architects that will gladly fill his shoes. In a ‘deconstructivist’ fashion, one can summarize this commonplace by saying that programme or function (and its ideological source) forms both the condition of possibility and impossibility of architecture. Today, many avant-garde architects heroically embrace this structurally decentred condition of architecture and shift their focus from interfering directly with ideologico-programmatic decisions which, so they argue, cannot be controlled anyway, to the formal aspects of architecture. By assessing the empirical conditions in which buildings come to be, the specific semantic levels in which buildings are inevitably enmeshed in a city, or by way of architectural-historical analysis, they try to establish an autonomous, absolute architecture – one that is no longer ‘troubled’ by decisions beyond its jurisdication. In short, they only focus on problems of a strictly architectural nature – problems of typology, form, space, circulation, light, material, etc. This legal-contractual interpretation of architecture’s agency obviously forecloses the possibility of a radical architecture, a fully politicized architecture that goes beyond what can be reasonably asked of it. Put differently, it rules out the possibility of an architecture that questions the criteria that determine what is reasonable and what is not since these criteria are not naturally given, but always determined by a ideological decision and thus political. It is precisely such an act that is being repressed by the ruling deontology of the new conservatives. They summon their colleagues to put their architectural expertise at the service of the interests and rights of the employer – just like a lawyer puts his juridical know-how at the disposal of his client.

4. From heroic realism to the realist hero

If Anca Petrescu is the spiritual mother of this new trend, Dutch architectural office Neutelings-Riedijk is the father. In a recent exhibition, they defined their position as a heroic realism. [17] This self-referential term serves as an excellent entry-point into the conceptual-ideological matrix of office Neutelings-Riedijk as well as the current architectural climate in the Netherlands. Paradigmatic in this regard is the office’s infamous entry in a competition for a concert hall in Bruges. Instead of compulsively questioning the programme or presuppositions of the employer, which for years was an obligatory task for radical architects, Neutelings-Riedijk remained very conservative and limited themselves to strictly architectural matters such as volume, form and materials. Symptomatic here is the way the office conceived the exterior of the building. On it they ‘copy-pasted’ the texture of Bruges’s number one tourist export product, their renowned lacework. The reasoning behind this formal-aesthetic decision is evident. Instead of attacking Bruges’s million dollar tourist industry head on – by opting for a modernist structure to mock Bruges’s pathetic architectural image of fake Medieval city – Neutelings-Riedijk chose for the inverse strategy by fully endorsing Bruges’s mythology. However, they did this in an unconventional, ‘tongue-in-cheek’ sort of way by blowing up the archetypical lacework motives to urban scale proportions and using them as decorative motif for the brickwork that covers the entire exterior surface of the building. In short, Neutelings-Riedijk’s intervention consisted in updating Bruges’s image, in applying a sort of ‘lacework in the age of mechanical reproduction’.

It is obvious why this is a good example of ‘heroic realism’. First, it is realist in that it does not attempt to intervene on the level of the programme of the building; it makes no effort to question or redefine the employer’s programme. This is a tendency that is gaining increasing ground among contemporary architects. If we scan the architectural field we encounter a myriad of justifications for this so-called realistic attitude. One often-heard reason is that the employer rarely accepts or appreciates such a negotiation of his needs and desires. More fundamental is the argument that programmatic interference smacks of demagogy. It is said to go against democratic principles since the architect forces his own beliefs and programmes on society and this in a building that belongs to the community. Behind this reproach is another popular topos, that of the architect as a totalitarian dictator who abuses his privileged position in the building process to realize his own aesthetic preferences, agendas and ideologies. Moreover, heroic realists are quick to add that in the time of the ‘End of all grand narratives’ there no longer exists a shared, positive, societal project that can legitimize such an intervention. In this context, any intervention of the architect on the level of programme cannot but be based on his personal opinion which is only one among many. For this reason it is seen as a virtue to push through one’s own convictions only with moderation and respect for others

With the latter, we encounter the most important move made by heroic realists: their ‘turn to reality’ is affirmed as a strength, as a form of heroism, as a victory upon its own hubris. Heroic realists claim that only through a realistic attitude can the architectural discipline be liberated from the heavy moral burden that it has taken upon itself for too long, which has prevented the architectural profession from fully exploring or realizing its own potential. In other words, they claim that only an architecture that modestly sticks to strictly architectural manipulations – an architecture within the limits of architecture alone so to speak – can realize the avant-garde constructivist dream: the enlightenment and transformation of man through architecture.

Although Neutelings-Riedijk’s entry was awarded second place in the competition, we should refrain for attributing this to its subversive quality. To be sure, the winning entree by Belgian architectural office Robbrecht & Daem was a far more traditional design – something which set the tone of the discussions in the media and among Bruges’s inhabitants: it appeared as if the modest-introvert Belgian had defeated the arrogant-provocative Dutchman. However, this obscures the fact that the fundamental architectural operation of both designs was the same. In the winning design it was not Bruges’s lacework but its typical red-brown terracotta roof-tiles that were used in an unconventional way to cover the exterior surface of the building. The debate was thus a pseudo-debate that hid the fact that both designs share the same fundamental position: without scruple both identify with the imaginary place carved out for it in Bruges’s city-marketing scheme. As everybody knows, the concert hall was one of the ‘grand projects’ of mayor Patrick Moenaert. It was meant to be the mantle piece of Bruges Cultural Capital of Europe 2002 – the ultimate city marketing scheme if ever there was one. With the new concert hall, Bruges set out to conquer a new niche: that of the contemporary cultural tourist who apart from consuming historical items wants to enjoy a lively, contemporary cultural scene. In this way the new fashioned concert hall was an attempt to break with its image of being a conservative nest where all normal urban life or activity is put on hold in function of its sole economic motor: tourism. The concert hall had to put Bruges on the map as a proud city that fully takes on the challenges demanded of cities in the 21st century.

However exciting this romance between realism and heroism might seem, its true political allegiance cannot be mistaken: it is part of the new wave of conservatism that has infected the contemporary architectural avant-garde. This is already apparent from the formal structure of the term ‘heroic realism’ as well as all other ‘isms’ that currently circulate to characterize the new engagement proper to contemporary avant-garde architects. Think for instance – apart from heroic realism – of terms such as ‘dirty realism’, ‘fresh conservatism’, ‘radical mediocrity’ or ‘dirty minimalism’. [18] The first striking feature is the fact that all these terms are comprised of two terms that are intuitively and conceptually incompatible. This clearly reveals the manifest belief among architects and theorists that the classic categories used to determine the political flavour of architectural design no longer hold in our late-capitalist present. If we go beyond this first impression of a confusion of terms however, we notice a constant behind these ‘isms’. To be more precise, the terms one would traditionally attribute to avant-gardist architecture – heroic, dirty, fresh, radical – are included as adjectives. Inversely, all tendencies that are normally perceived as reactionary – realism, conservatism, mediocrity, minimalism – are incorporated as nouns. This means that the progressive term is used to characterize the way in which the conservative term is executed. For example, one is conservative but in a fresh way, mediocre but in a radical way and so on. This systematic downplaying of the progressive term is symptomatic for the new engagement in architecture: despite its mixed, hybrid character the true conservative essence of contemporary architecture is easily distinguishable.

In an age in which architecture increasingly disappears in the marketing schemes of municipalities and real estate developers it is very urgent to invert this hierarchy and push the conservative terms into the adjective position. In other words, what is needed today are architects with fresh ideas without a conservative impulse or a radical architectural movement that is not afraid of resorting to very realistic, conservative or dirty tactics to implement these ideas. In short, we need a ‘realist hero’, instead of a ‘heroic realist’. Although this might seem like a negligible modification, it is this very minimal difference that is fundamental for architecture to reconquer its subversive potential.

5. In Lagos, children don’t cry

One of the crucial references for understanding heroic realism is an early project by Rem Koolhaas – another founding father of contemporary avant-garde architecture in the Netherlands – entitled Exodus, or, the voluntary prisoners of architecture. [19] This project sets out a conceptual scheme – worked out in text and collage – for a huge superstructure erected above the metropolitan area of London. According to Koolhaas’s vision, people would voluntarily strip themselves of all their rights and possessions to be able to experience the architectural intensities and experiments taking place in this gigantic dark room. The project should be seen as part of Koolhaas’s criticism against the weak-hearted humanism of modernism à la Team X – a movement that was itself already a criticism of orthodox CIAM modernism. This criticism, dominant since the late fifties, culminated in the Situationist movement. It is therefore no coincidence that Koolhaas’s superstructure looks like a copy of the ‘sectors’ of Constant’s New Babylon. The legal striptease to which the crowds voluntarily subject themselves in Koolhaas’s Exodus are off course the same rights – air, light, space, greenery, etc. – that generations of modernists had projected onto the urban field.

The thing not to miss in this architectural fairy-tale is how the concept of voluntary servitude is radically inverted. In the original of Etienne de la Boétie it functions as the cornerstone of a rather dark, anti-progressivist, pessimistic vision that detects something in humankind that repeatedly desires its own subordination. [20]. In other words, it pointed to an enigmatic inertia in man that makes him resist his emancipation and avoid a confrontation with his radical freedom. Although Koolhaas criticizes the progressivist, emancipatory discourse of modernism, he attaches a much more affirmative meaning to the concept of voluntary imprisonment. In his view, the voluntary prisoner of architecture is a type of urban dweller that no longer lets himself be caught in the moralism of generations of modernist planners. It is somebody who no longer asks of the architects to guarantee a minimal quality of life or to prevent and fix every possible nuisance in his habitat. On the contrary, it is a dweller that voluntarily ignores all the accomplishments of modernity and is willing to risk all of these all too human things for the intensification and multiplication of his kicks – which in Koolhaas’s scheme also include architectural kicks. Koolhaas’s point is that modernism developed in a too pastoral direction, into “an urbanism for the socially and physically handicapped” [21] in which the architect treats the urban populations as weak and pitiful beings that have to be kept biologically, physically and morally healthy. To put it in Freudian terms, modernism overemphasized homeostasis, ignoring or underestimating the erotic or death drive in humankind. Koolhaas’s remedy is obvious: the new modernists should rather conceive of the metropolitan multitudes as Nietzschean figures who do not fear the deterritorializations caused by the globalization and commodification of the urban environment but, on the contrary, affirm it as ways to organize their pleasure in ever more elaborate and intense ways.

This vision has become without doubt the gospel for the architectural avant-garde today or at least for the new generation of fresh conservatives, heroic realists and so on. Whether it concerns skyscrapers, pseudo Medieval cities, shopping malls, African megapolises, the inhabitants of problem neighbourhoods, homeless people or illegal inhabitants, in the discourse of today’s avant-garde architects they are all immediately rewritten as voluntary prisoners. It is argued that only to an outsider, these people might seem condemned to life in inhumane situations, and thus become an object of pity or disgust. Against this, the heroic realist – obviously an ‘insider’ – firmly claims that if you would ask these people themselves, they would not want to trade their lifestyle with any other. In short, the proponents of Koolhaas’s philosophy of voluntary imprisonment claim that most of the present-day metropolitan problems only exist in ‘the eye of the beholder’. They are products of the prejudice of the architect, which in turn is linked to his position in society. As a consequence, any critical or non-affirmative attitude towards these marginal groups is seen by most of today’s cutting edge architects as a stubborn ideological distortion that has to be exorcized at all costs.

What is so problematic about this thesis of the voluntary prisoners of architecture and the way it is practiced by the majority of progressive architects? In one of OMA’s recent exhibitions in the Kunsthal in Rotterdam, a documentary was shown in which an exalted Koolhaas claims that he has never seen any children crying in the African megalopolis of Lagos. [22] This anecdote is exemplary for Koolhaas’s analysis of this Third world city which according to him provides us with the conceptual toolbox for a contemporary architectural avant-garde praxis. [23] He for instance provocatively claims that “Lagos represents a developed, extreme, paradigmatic case-study of a city at the forefront of globalizing modernity. … Lagos is not catching up with us. Rather we may be catching up with Lagos.” [24] The anecdote about the ‘not crying’ children of Lagos clearly reveals the dubious stance of Koolhaas’s thesis of the voluntary prisoners. One detects an uncanny resonance with the neo-colonialism of Westerners commentating on the big libido of Africans, their huge genitals, their unrivalled rhythmic feel or their athletic capacities. Or, the common assumption that people living in slums – think of the Brazilian favelas – after all live a more spontaneous live and are happier than us neurotic control freaks in the West. Between the lines of these clichés a clear moral prohibition can be read, urging us not to mess up their supposed happiness by interfering politically or economically in processes that might appear inhumane to us Westerners.

Let me repeat this point with the aid of another example. I don’t think it is a coincidence that in today’s designer’s circles or the enlightened cultural scene in general there is such a flirting going on with pornography. The aesthetic of ‘hustlers & pimps’ or the wild and ‘juicy’ lifestyle of porn stars has become the theme for many a culturally correct party, the dress-code of the urban avant-garde and even an inspiration for cutting-edge architectural details. [25] The ideological nature behind this fascination becomes obvious if we regard the porn-star as the ultimate voluntary prisoner. Today, only a retarded moralist can still seriously claim that porn-stars are victims of a ruthless and perverted industry and suggest that it would be better for them to have a monogamist, straight relationship, to enjoy the satisfaction of working in the household or of having a straight job. Such criticism can easily be countered by the question of who is in fact imprisoned here: the critic or the porn star? Of course, porn stars themselves usually promote their job as a dream-job – preferable any day to the imprisonment of a normal, institutionalized marriage. Still, is this presentation of the so-called facts not rather cynical in a time in which children are bombarded from an early age by perverse sexual demands through advertisements, video clips or television series that are carefully designed by an entire industry? Even if youngsters dress up voluntarily like ‘hustlers and pimps’ is it not rather the existing system of economic and power relations that wants this through them? The adjective ‘voluntary’ loses all meaning here since the subject is on a more fundamental level deprived of its will. Or put differently, the subject is unconsciously made to want it.

6. It’s about a voluntary imprisonment ‘with a will’, stupid!

The first step to break with the present conservative architectural climate is to make Koolhaas’s concept more precise by speaking instead of a voluntary imprisonment without a will. Seen from this perspective,the heroic realist architect – voluntarily imprisoning himself in conservative architectural phenomena such as shopping centres and tourist industries – appears in a different light. It is clear that with the copy-pasting of all kinds of reactionary architectural elements the architect also sacrifices his initial will to politicize the antagonisms behind these phenomena. However, instead of rejecting this strategy altogether, we need a selective or strategic affirmation of conservative architectural codes and structures. After all, even if one sees in realism the only way out, even if the only opportunity for an avant-garde architectural project today is to be found in heroically endorsing the prevailing architectural programmes, this does not free the architect from thinking strategically. Can these reactionary architectural phenomena not serve as a vehicle for provoking and subverting the underlying ideological processes? And does such a selectively affirmation not enable architecture to be critical while at the same time accept the demands of the employer? In short, even if it seems impossible today not to relate to the dominant programmes or forms, the architect can still choose to become a voluntary prisoner with a will.

To make this strategy concrete, we can refer to a project by Belgian architect, Wim Cuyvers. It concerns a stereotypical Belgian housing project: a free-standing single family house nestled in a small condominium of houses. [26] These condominiums usually prescribe certain rules for the design of the houses. Relevant here is the fact that the building materials had to be ‘region-specific’, which – as every Belgian architect knows – is but another term for rustic bricks and terracotta roof-tiles. Apart from that, another important element to know is the fact that the client could hardly afford the property not to mention any additional building costs. The architect thus had to find the cheapest possible solution. Further, the project is situated in a heterogeneous landscape of condominiums, huges blocks of industrial greenhouses as well as canning factories – the type of area known in architectural circles as the ‘In-between-land’. [27] What is particularly celebrated is these sorts of areas is its heterotopic and dirty character, the fact that it is both rural and urban, vernacular and high-tech, traditional and industrial. Cuyvers’design seems to have negotiated all these factors by designing the house in, what you could call, a Le Corbusian way, a ‘greenhouse for living’. The house consists of a huge cubic industrial greenhouse construction containing all the living functions. One of the reasons for this choice is that an industrial greenhouse construction is a very cheap way of building while allowing, at the same time, for huge living surfaces and an experimental lay-out for the housing programme.

Apart from these, what you could call, internal design affairs, the materials and construction method were also chosen in order to intervene in the context. That the latter was achieved was already clear from the violent debate Cuyvers’s greenhouse stirred with the surrounding house-owners as well as the municipality. The latter accused the design for being a barbaric architectural act with total disrespect for the regional building tradition. Still, legally speaking they could not prevent this design from being built since the greenhouse seems to inversely accuse the other pseudo rustic houses from being disharmonic elements in a landscape governed by industrial greenhouses. Thus opening a debate on the relativity of what people spontaneously experience as their architectural identity.

The strategic genius of this house is that through a strictly architectural intervention political issues were addressed and worked through. In the first place, the tension between the ‘Belgian cottage’ as symbol of the anarchist radical-democratic Belgian housing culture on the one hand, and the network of formal and informal building regulations that keep building costs unnecessary high on the other. It is clear that with this, only the upper middleclass is allowed to satisfy its anarchist drive and further that it mainly benefits Belgium’s brick capitalists. In the second place the house reveals the split nature of its context: the so-called In-between-land. It reveals how an architectural conservatism celebrating the traditions of rural life forecloses the ‘Real’ industrial-economic processes, not allowing for any hybrid forms to be developed. However, in both cases Cuyvers’s greenhouse goes further than simply staging the contradictions of the context or mirroring them. The building functions rather as an unbearable knot that creates a short-circuit between all parties of the ‘in-between-land’ and forces them to choose sides. The house has such a suffocating effect because it reveals how the many differences of the area are based on a deeper identity. In the first case, the fact that the anarchist-libertarian ideal of having one’s own cottage is only possible through a juridical-economic set of rules that secures the exclusivity of the own enclave. In the second place, the house shows how the peaceful condominiums deny their condition of possibility: the industrial horticulture that first make them possible because they support the region economically. By revealing the underlying relations of dependence the building reveals the superficiality of the heterotopic tensions of this ‘in-between land’.

Let me end by bending this discussion back to the new conservatism in architecture I have problematized above. What makes of the design of Cuyvers an act of a realist hero is that through a purely formal architectural invention – which is what Untitled and Neutelings & Riedijk plea for – he politicizes the political and economical inconsistencies typical for Belgian housing ideology. On top of that, Cuyvers’s building proves that such an architectural act is not necessarily at the expense of the client and its interests and rights. Neither does the architect herewith commit ‘professional suicide’. Let alone that it implied a return to an elitist architecture. Firstly, the architect’s statement was clearly understood by all parties involved. Secondly, the ‘greenhouse house’ also offers a realistic alternative both economically, ecologically and spatial for the dominant building praxis. In short, all disaster scenario’s that keep the new conservatists from doing more than facilitating the demands of the employer, proved in this case to be mere phantasmatic constructions that are meant to legitimize one’s own passivity. In this sense, the house reveals how architectural formalism does not exclude political intervention.

If architecture wants to take up its avant-gardist mission again and subvert society from within, it is only possible in such a precise, selective and political-strategic over-identification with existing architectural codes. However, to achieve this, one cannot avoid to play political games, dirty the formal purity of architecture or, in short, to put at stake the absolute character of architecture. We have to be very precise here. Our criticism of the new conservatives is not just that an architecture that wants to stay far away from ideological games and remain on its own level – an absolute architecture so to say – cannot escape recuperation by the regime in which it is embedded. Rather than eradicating all hope for a radical architecture, the point is that this recuperation takes place precisely when it takes as its objective such a naïve pseudo-avant-gardist longing for a pure architecture. Cuyvers’s greenhouse house on the contrary proves that it is more strategic to depart from the opposite premise. Through a deformation of a statement of the Slovenian avant-garde rock-band Laibach, we can determine the latter as follows: all architecture is subjected to political or economical manipulation except for that which speaks the language of the same manipulation. [28]

NOTES

1. http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,885724,00.html#article_continue

2. See the essayas ‘Do-It-Yourself’ and ‘Architecture against Architecture’ by Roemer van Toorn, www.xs4all.nl/~rvtoorn

3..See PhD thesis entitled The Possibility of Absolute Architecture, defended at the T.U.Delft, 10/10/2005

4. See ‘Architecture is itself’ in the program brochure 35m3 young architecture, Office K.G.D.V.S., De Singel/VAi; pp. 16-33; see also ‘DTN#2, Architecture is itself! DTN#2 in gesprek met Eleni Gigantes & Elia Zenghelis’, in AS no.161, 2002, pp.70-81

5. Written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999

6. Untitled consists of Kersten Geers, David van Severen, Bas Princen and Milica Topalovic

7. Fear & Space, NAi Publishers 2004, p.110

8. Ibid., p. 156.

9. Ibid., p. 94.

10. Ibid., p. 85.

11. Ibid., p. 85.

12. Slavoj Zizek, Ticklish Subject, Verso 1999, p.215

13. Rem Koolhaas Delirious New York, 010-Publishers 1994

14. Witte de With Rotterdam, 11/12/2004. See also Dieter Lesage ‘Metropolitane Machinaties’, in Metropolis M no. 2, 2005, p.80-83

15. It is a significant anecdote that when Petrescu went into hiding in Paris after the regime change she built tourist palaces for the Club Med in Florida – other elite, same position.

16. He made these claims during the television programme RAM on Dutch public television channel Nederland 3, 29/02/2004

17. Exhibition Behind the Curtains: Fifteen Buildings by Neutelings Riedijk Architects, in the Netherlands Architecture Institute, spring 2004.

18. Respectively: Rem Koolhaas in S,M,L,XL, 010-publishers 1997, pp. 570-577; Roemer Van Toorn ‘Fresh Conservatism, Landscapes of Normality’, 1997 (www.xs4all.nl/~rvtoorn); Henk Oosterling Radicale Middelmatigheid, Boom 2000; Wouter Vanstiphout ‘Dirty Minimalism”, in Archis, no. 5, 2004, pp. 76-79.

19. See, Rem Koolhaas S,M,L,XL, 010-publishers 1997, pp. 2-21

20. See Etienne de la Boétie The Politics of Obedience: the Discourse of Voluntary Servitude, Black Rose Books 1975.

21. Rem Koolhaas Bijlmerstrip, Technische Universiteit, 1977, p.4

22. Exhibition Content, in the Kunsthal, Spring 2004

23. Rem Koolhaas, Mutations, ACTAR 2000

24. Ibid., p.653

25. See Roemer van Toorn ‘Dirty details’, www.xs4all.nl/~rvtoorn

26. Gits, Belgium 2000

27. Ruimtelijk Planbureau, Tussenland Nai Publishers 2004. See also: Dieter Hamers, ‘Nederland Tussenland’, in: Filosofie Magazine no.2, 2005

28. See Laibach’s convenant of Trbovlje, 1982 at: www.nskstate.com

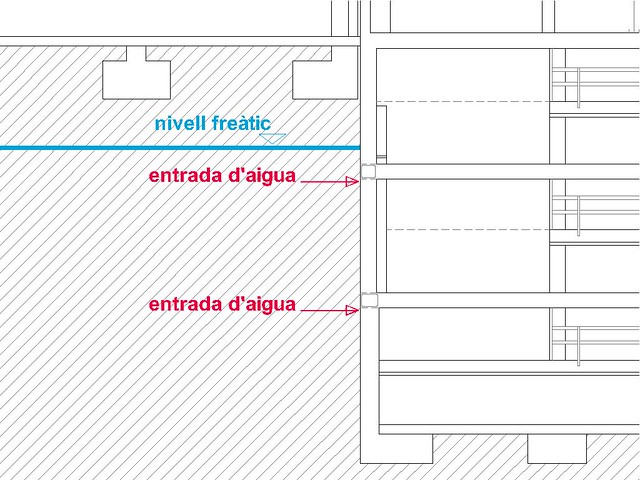

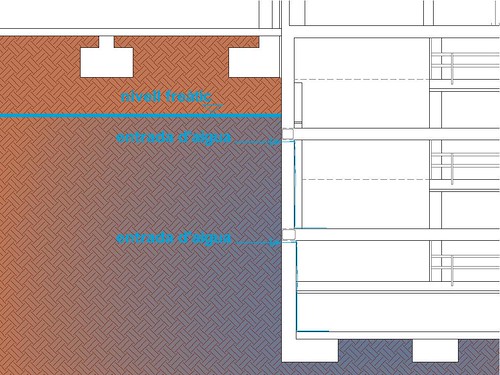

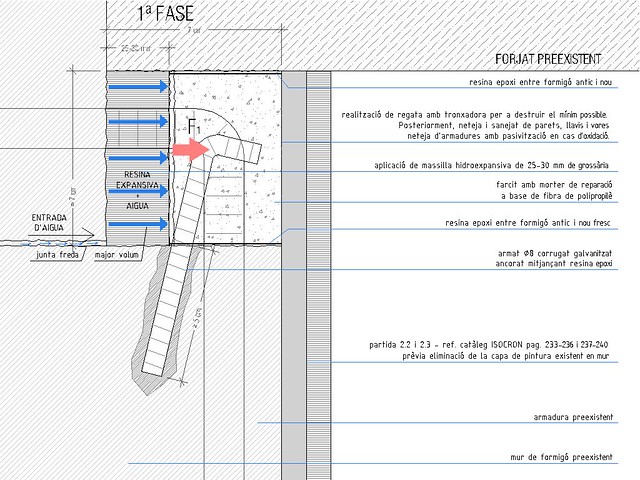

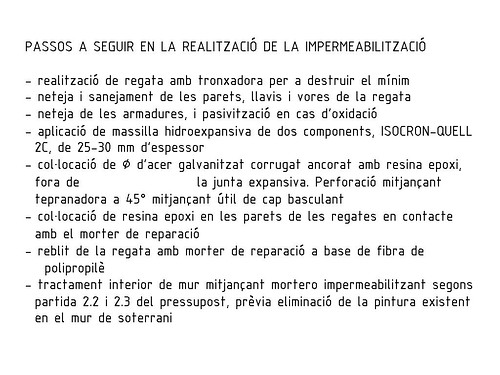

La Junta de Govern Local del passat 21 de juny, a

La Junta de Govern Local del passat 21 de juny, a El projecte executat fins a dia de hui, contava amb el

El projecte executat fins a dia de hui, contava amb el Fins a dia de hui s’han executat 4 fases, per un import

Fins a dia de hui s’han executat 4 fases, per un import Quan s’acabà la 4 fase, l’Alcalde Joan Baldoví

Quan s’acabà la 4 fase, l’Alcalde Joan Baldoví Les diferències entre el que ara es vol fer i el que es

Les diferències entre el que ara es vol fer i el que es