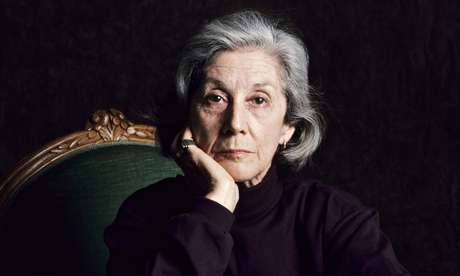

South Africa has produced several writers of stature in the past half century, but few have approached the achievement of Nadine Gordimer, who has died aged 90. A significant figure in world literature, Gordimer plumbed the depths of human interaction in a society of racial tension, political oppression and sexual unease. The connection between the intimate and the public lay at the heart of her work, an apparently inexhaustible stream of novels, short stories and essays.

An outspoken voice against the evils of apartheid, Gordimer continued to express forthright views after its collapse and the emergence of a multiracial democracy. Promoting even as she questioned white liberal values in her early work, she went on to espouse an increasingly radical position in the essays and fiction of the mid-1970s and later, openly supporting the liberation movement and associated cultural bodies such as the Congress of South African Writers. This led to her being for many years more widely acclaimed abroad than at home – where several of her novels were banned – until she became in 1991 the country’s first winner of the Nobel prize for literature.

When the Swedish academy made its award, it announced that it was for her “great, epic writings centring on the effects of race relations in her country”. While it is true to suggest that the focus of her work was on relationships between the races, her careful probing of what happens to people under the pressures created by the prevailing structures of power represents a larger achievement, that of a writer in touch with the broad movements of history and their impact upon society.

Yet the force of Gordimer’s work comes from its testimony to the quality of life in South Africa. It was, she said, “learning to write”, rather than waking up to “the shameful enormity of the colour bar” through joining any political party, that sent her “falling, falling through the surface of ‘the South African way of life'”. As she once remarked, every white South African needs to be born twice: the second time into an awareness of the profound racism in which they first found themselves.

Gordimer’s writing career took off during the late 40s and early 50s with the publication of short stories in South African liberal and literary magazines, followed by international journals such as, crucially, the New Yorker, whose continued support from 1951 provided much encouragement for the young writer, while helping to create a wider public for her work. These early stories, clever and perceptive as they were, did little more than display the inner thoughts of white middle-class characters trapped in a world about which they felt guilty, but that they did not understand.

She went on to write more than 200 stories, expanding her range while concentrating her focus in a truly remarkable series of collections, from Not for Publication (1965) and Livingstone’s Companions (1971) to Jump (1991), Loot (2003) and Life Times (2011, a collection spanning 55 years of writing). She experimented towards the end, not always successfully, with symbol and allegory, and but for her success as a novelist would have been remembered as a great master of the short-story genre, which she always defended for its concentration, integrity and lack of compromise.

Her first published novel, The Lying Days (1953), a semi-autobiographical Bildungsroman, did little more than hint at a more challenging awareness of her fragmented colonial background. The succeeding novels, A World of Strangers (1958), Occasion for Loving (1963) and The Late Bourgeois World (1966), however, cemented her reputation as a novelist able to chart with a new immediacy and depth the failures of love and morality in the corrupting and limited world of colonial relations.

At times, Gordimer seemed to feel that she was forging her literary path alone, and that the novelist in South Africa “does not live in a community and has begun to write from scratch at the wrong time”. Despite the influential work of her compatriots Olive Schreiner, Alan Paton and Dan Jacobson, and the first novel in English by a black South African, Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi, Gordimer always looked towards the novels of her European predecessors, from George Eliot to Henry James, DH Lawrence and Proust.

She gradually developed an aesthetic of her own, developing beyond the predominantly social realist, liberal-conservative fiction of her early works, to the more radically modern, indeed modernist writing of The Conservationist (1974), joint winner of the Booker prize and perhaps her greatest achievement. With The Late Bourgeois World, A Guest of Honour (1970) and Burger’s Daughter (1979), it had become became clear that whatever the limitations of her chosen setting and focus, Gordimer was one of the great political novelists of the time.

For all South Africans, 1960 and the Sharpeville massacre marked a watershed; for Gordimer, the arrest of her best friend, Bettie du Toit, led to a more active involvement in politics. She joined the ANC while it was still illegal to do so, having befriended two of the lawyers defending Nelson Mandela, George Bizos and Bram Fischer, to whom Burger’s Daughter was a “coded homage”. She went on to assist the movement, often in secret.

As resistance was being crushed by an increasingly vicious state, Gordimer’s exploration of the impact upon the lives around her deepened her writing, leading to a more complex interweaving of narrative voices so as to include political speeches and documents as well as the secret interior thoughts of her characters – notably Mehring, the wealthy white industrialist and “conservationist” of that novel’s title. Mehring’s consciousness is at the centre of the novel, which reveals in precise and haunting detail his struggles to keep change at bay, while exploiting everyone in his power, from the young Portuguese girl beside him on a flight to the workers on his farm. A tissue of allusions to the indigenous African culture he unconsciously seeks to destroy while avoiding his own complicity undermines his attempts to conserve his wealth and his sense of himself, anticipating the collapse of white supremacy.

The increasingly polarised situation in South Africa after the 70s led to the semi-allegorical and strained July’s People (1981), a revisiting of the master-servant relationship upon which so much of her work dwelt. But with the demise of apartheid, Gordimer once more showed her strength, challenging the supposed anxiety for writers in her country that they now lacked a subject, with The House Gun (1997) and her award-winning 2001 novel The Pickup, which exposed the new issues of migration, corruption, and continuing alienation. Her more recent work, such as Get a Life (2005) and No Time Like the Present (2012), although deft and assured, was increasingly impersonal, while continuing to pursue the dilemmas of a post-apartheid generation trying to come to terms with the present.

Gordimer was born in the small East Rand mining town of Springs, the daughter of Jewish immigrants. Her mother, Hannah (“Nan”) Myers, came from London; her father, Isidore, left Latvia as a teenager to “escape pogroms and poverty” and join his watchmaker brother, later becoming a flourishing jeweller. The immigrant Jewish group features as an identifiable presence in Gordimer’s work, yet she was raised in a secular household, and to begin with was educated in a Catholic convent school, from which her mother removed her for “strange reasons of her own”, claiming her daughter had a heart condition.

Living at home, Gordimer read voraciously and began writing, publishing her first stories at the age of 15, and her first adult fiction a year later. She studied for a year at the University of Witwatersrand, where she made her first friendships across the “colour bar”, in particular encountering the vibrant but fast disappearing multiracial world of Sophiatown, where she met influential black writers and intellectuals such as Es’kia Mphahalele, Nat Nakasa, Todd Matshikiza and Lewis Nkosi. She did not complete her degree, but moved permanently to Johannesburg in 1948.

The city remained her home, despite the often involuntary departures overseas of many friends and associates and eventually her two children. Her first marriage, to Gerald Gavron, by whom she had a daughter, did not last. In 1954 she married Reinhold Cassirer, a wealthy art dealer with whom she had a son. She was tempted to leave South Africa on more than one occasion; but her instincts as a writer as well as her political convictions led her to remain firmly rooted where she was, living, as she put it in an influential lecture, “at six thousand feet in a society whirling, stamping, swaying with the force of revolutionary change” (Living in the Interregnum, 1982). This visionary awareness occasionally surfaces in her work, which otherwise reveals a more pragmatic, sometimes pessimistic approach to her characters and their failings.

Of her innumerable reviewers and many critics, one of the best, Stephen Clingman, edited a stimulating collection of her essays, The Essential Gesture (1988), which reveals a rigorous analysis of the politics of writing in her country, in particular her unequivocal stand on censorship and her forthright support for the community of all South African writers. In 2005 a biography, No Cold Kitchen, was published by Ronald Suresh Roberts, who had been granted interviews and access to her papers on the understanding that she would authorise his book in return for the right to pre-publication review. However, biographer and subject fell out, and Gordimer disowned the book. It remains an invaluable resource, if to be treated with caution.

Gordimer addressed the moral and political dilemmas of her own and her children’s generations in a society finally released from the terrible grip of an extraordinary form of control and exploitation. She did not share the profound disillusion of writers such as JM Coetzee, while admitting the problems brought by the new dispensation in her country. As she had thought, a “change of consciousness” had to accompany a change of regime. She examined the inevitable compromises and betrayals within individual lives of privilege, struggle and freedom, providing in the course of 15 novels the possibility of understanding, if not achieving, a humane life.

Cassirer died in 2001. Gordimer is survived by her daughter, Oriane, and son, Hugo.

• Nadine Gordimer, writer, born 20 November 1923; died 13 July 2014