Vindicació del dibuix manual per Michael Graves en un article del NYT

Deixa un comentariRegirant i escorcollant el New York Times em trobe un article de l’arquitecte postmodern Michael Graves. Datat en 2012-IX-01. Però, malgrat que trobe unes distàncies enormes entre els seus pressupòsits -socials i formals- i els meus, m’ha fet gràcia la coincidència de reblar la idea de qui dibuixa no és la mà sinó la interconenxió entre el cervell i la mà. Vindicant simultàniament el paper dels ordinadors cal no deixar de banda aquest aprenentatge. Ha dividit els dibuixos en tres classes. L’esbós-idea, el dibuix de definició conceptual i el d’acabament per ordinador.

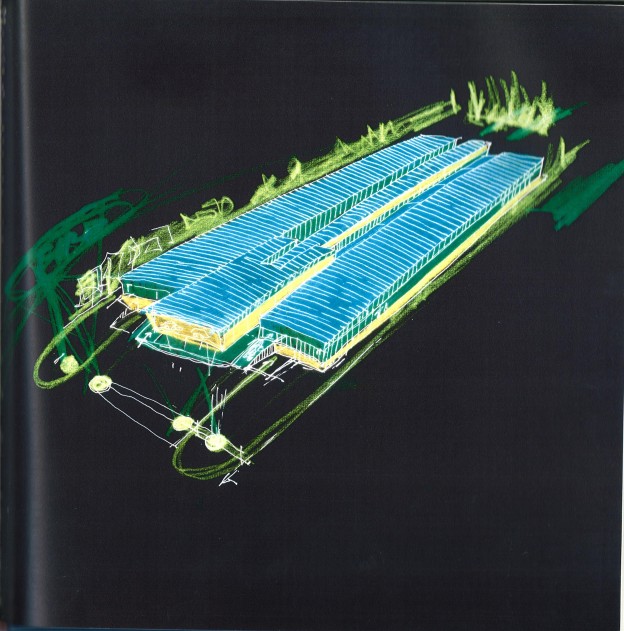

Tot i que aquest dibuix segon – dibuix de planta fet amb amb ordinador- cal no oblidar-hi que la idea procedeix d’aquella perspectiva del primer feta a mà alçada en cinc minuts. I que, en certa mesura, són indestriables.

Vos dese un slide de dibuixos triats per ell, que gens o poc s’assemblen amb els de l’arquitectura avançada.

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2012/09/02/opinion/sunday/20120902-Graves-Drawing.html?smid=pl-share

Si el voleu llegir directament cliqueu sobre l’enllaç. I si no, us l’he copiat a dessota directament.

L’enllaç ací

IT has become fashionable in many architectural circles to declare the death of drawing. What has happened to our profession, and our art, to cause the supposed end of our most powerful means of conceptualizing and representing architecture?

The computer, of course. With its tremendous ability to organize and present data, the computer is transforming every aspect of how architects work, from sketching their first impressions of an idea to creating complex construction documents for contractors. For centuries, the noun “digit” (from the Latin “digitus”) has been defined as “finger,” but now its adjectival form, “digital,” relates to data. Are our hands becoming obsolete as creative tools? Are they being replaced by machines? And where does that leave the architectural creative process?

Today architects typically use computer-aided design software with names like AutoCAD and Revit, a tool for “building information modeling.” Buildings are no longer just designed visually and spatially; they are “computed” via interconnected databases.

I’ve been practicing architecture since 1964, and my office is not immune. Like most architects, we routinely use these and other software programs, especially for construction documents, but also for developing designs and making presentations. There’s nothing inherently problematic about that, as long as it’s not just that.

Architecture cannot divorce itself from drawing, no matter how impressive the technology gets. Drawings are not just end products: they are part of the thought process of architectural design. Drawings express the interaction of our minds, eyes and hands. This last statement is absolutely crucial to the difference between those who draw to conceptualize architecture and those who use the computer.

Of course, in some sense drawing can’t be dead: there is a vast market for the original work of respected architects. I have had several one-man shows in galleries and museums in New York and elsewhere, and my drawings can be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Cooper-Hewitt.

But can the value of drawings be simply that of a collector’s artifact or a pretty picture? No. I have a real purpose in making each drawing, either to remember something or to study something. Each one is part of a process and not an end in itself. I’m personally fascinated not just by what architects choose to draw but also by what they choose not to draw.

For decades I have argued that architectural drawing can be divided into three types, which I call the “referential sketch,” the “preparatory study” and the “definitive drawing.” The definitive drawing, the final and most developed of the three, is almost universally produced on the computer nowadays, and that is appropriate. But what about the other two? What is their value in the creative process? What can they teach us?

The referential sketch serves as a visual diary, a record of an architect’s discovery. It can be as simple as a shorthand notation of a design concept or can describe details of a larger composition. It might not even be a drawing that relates to a building or any time in history. It’s not likely to represent “reality,” but rather to capture an idea.

These sketches are thus inherently fragmentary and selective. When I draw something, I remember it. The drawing is a reminder of the idea that caused me to record it in the first place. That visceral connection, that thought process, cannot be replicated by a computer.

The second type of drawing, the preparatory study, is typically part of a progression of drawings that elaborate a design. Like the referential sketch, it may not reflect a linear process. (I find computer-aided design much more linear.) I personally like to draw on translucent yellow tracing paper, which allows me to layer one drawing on top of another, building on what I’ve drawn before and, again, creating a personal, emotional connection with the work.

With both of these types of drawings, there is a certain joy in their creation, which comes from the interaction between the mind and the hand. Our physical and mental interactions with drawings are formative acts. In a handmade drawing, whether on an electronic tablet or on paper, there are intonations, traces of intentions and speculation. This is not unlike the way a musician might intone a note or how a riff in jazz would be understood subliminally and put a smile on your face.

I find this quite different from today’s “parametric design,” which allows the computer to generate form from a set of instructions, sometimes resulting in so-called blob architecture. The designs are complex and interesting in their own way, but they lack the emotional content of a design derived from hand.

Years ago I was sitting in a rather boring faculty meeting at Princeton. To pass the time, I pulled out my pad to start drawing a plan, probably of some building I was designing. An equally bored colleague was watching me, amused. I came to a point of indecision and passed the pad to him. He added a few lines and passed it back.

The game was on. Back and forth we went, drawing five lines each, then four and so on.

While we didn’t speak, we were engaged in a dialogue over this plan and we understood each other perfectly. I suppose that you could have a debate like that with words, but it would have been entirely different. Our game was not about winners or losers, but about a shared language. We had a genuine love for making this drawing. There was an insistence, by the act of drawing, that the composition would stay open, that the speculation would stay “wet” in the sense of a painting. Our plan was without scale and we could as easily have been drawing a domestic building as a portion of a city. It was the act of drawing that allowed us to speculate.

As I work with my computer-savvy students and staff today, I notice that something is lost when they draw only on the computer. It is analogous to hearing the words of a novel read aloud, when reading them on paper allows us to daydream a little, to make associations beyond the literal sentences on the page. Similarly, drawing by hand stimulates the imagination and allows us to speculate about ideas, a good sign that we’re truly alive.

Michael Graves is an architect and an emeritus professor at Princeton.

*************************************************************************

Després s’ha creat controvèrsia:

-

Architect

I have to say that this subject is completely overused (specially in my faculty). It has been more than proven that one this does not lead to the other regarding the use of technology and the use of drawing. It’s a matter of formation and how the architect was taught how to think.

I, for once, cannot think without a pen and a paper in my hand, but cannot imagine a world where I cannot use a computer for my work.

This said, I also have to remark that Michael Graves’ architecture is not very good.

- Like (3)

- Reply privately

- Flag as inappropriate

- 8 hours ago

-

Architect

Architecture and the Lost Art of talent, imagination, personal mark, artistic expression.

- Like (1)

- Reply privately

- Flag as inappropriate

- 6 hours ago

Ghadir M. likes this

-

Wilhelm Krüger Argitekte

I think the – art of drawing – is extemely important for the developing of good design, The hand drawing action uses the brain activity of designing on a beter level. Thereafter we have the wonderful world of the computer to encapture this and make it easy usable.

- Unlike

- Reply privately

- Flag as inappropriate

- 4 hours ago

-

Owner, hans moor architects and Design Specialist

Both drawing and computer have a different way of thinking. Bij computer most of the time you designing 3D. Drawing has more direct and fast access to conceptual thinking. A drawing doesn’t have to be a model, section or floorplan.

I like to do both – here you have an example of experimental- conceptual thinking by drawing and computer 3D https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i4xxGc_otG8- Like

- Reply privately

- Flag as inappropriate

- 3 hours ago

-

Wilhelm Krüger Argitekte

True. I think that is why it is neccesary to do both to achieve a good design.

- Like

- Reply privately

- Flag as inappropriate

- 2 hours ago